A wandering minstrel, Ashik Kerib, presents himself inside the frescoed partitions of Nadir Pasha’s “divan” (reception corridor). “I’m a humble minstrel. My lute and I are able to sing praises for you,” Ashik Kerib states. Nadir Pasha, a small-time nobleman, is an image of pantomime pomposity, sporting a curly mustache and quivering jowls. He’s bedecked in velvet and brocade; on his head bobs an outsized turban. Seated cross-legged to his proper, his wives coyly secrete themselves beneath coloured silk “kelahagyi” (scarves). When Ashik Kerib, in an indication of deference, bows his head to the carpet on the pasha’s ft, the ladies solid their kelahagyi apart, brandishing toy machine weapons that they hearth with abandon towards the ceiling.

That is considered one of a number of surprising moments in Armenian director Sergei Parajanov’s remaining film, “Ashik Kerib,” shot in Azerbaijan. These aware of his work know Parajanov had a penchant for inserting confounding objects, usually infused with obscure symbolism, into pivotal scenes. In Parajanov’s films, seaside umbrellas, nautilus shells and two-headed papier-mache tigers seem within the mountain landscapes of the Caucasus. “The Colour of Pomegranates,” his interpretation of the lifetime of the Armenian bard Sayat-Nova, encompasses a cameo function for a llama. In “The Legend of Suram Fortress,” a story of medieval Georgia, trendy oil tankers float on the Black Sea.

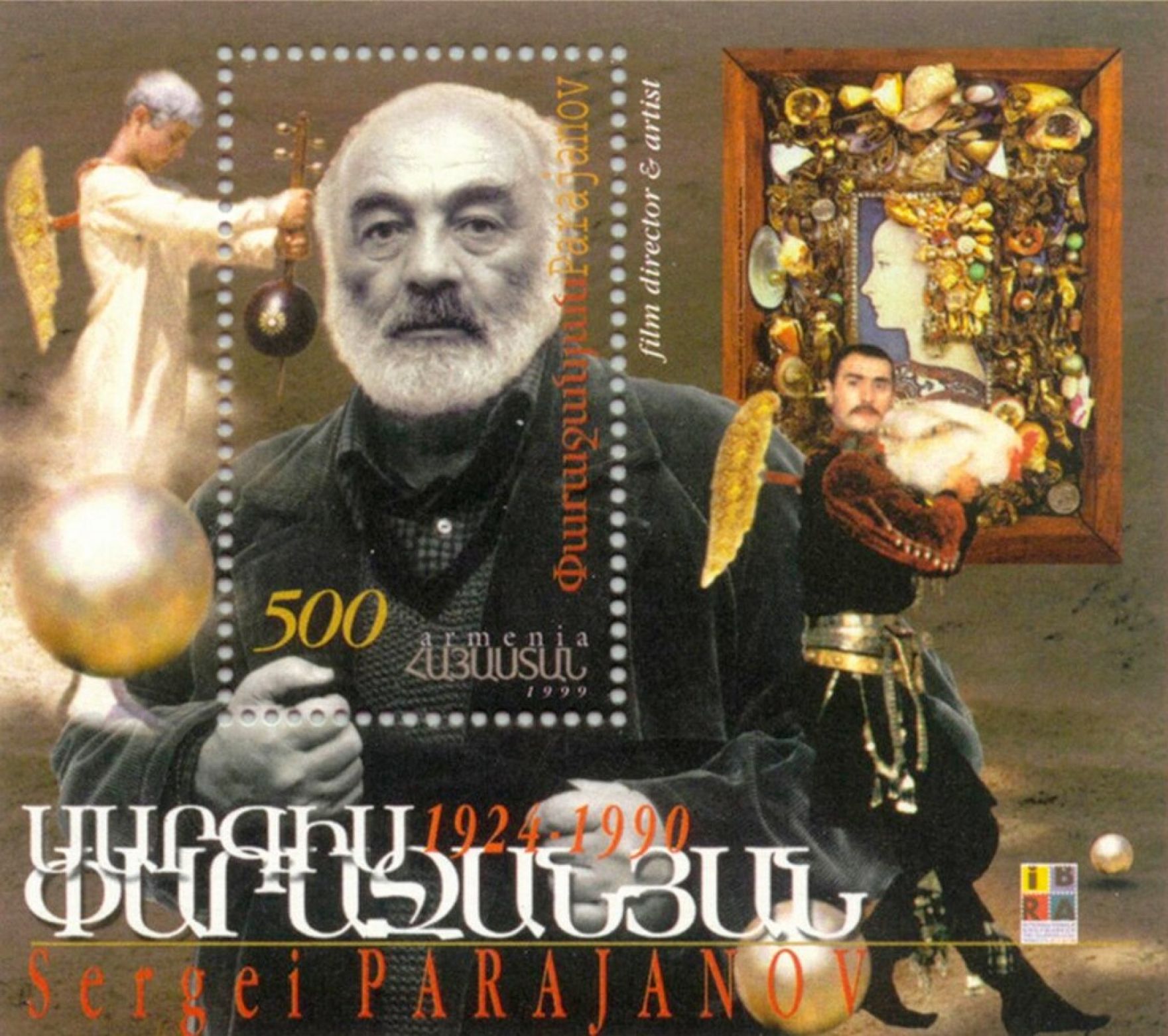

Via these movies, generally known as his “Caucasian Trilogy,” and others, Parajanov constructed a repute as probably the most ingenious filmmakers in cinema historical past. Born 100 years in the past in Tbilisi, Georgia, then a part of the Soviet Union, and dealing underneath the auspices of the Soviet State Committee for Cinematography, Parajanov created a comparatively small physique of labor, however he articulated a extremely idiosyncratic creative imaginative and prescient, successful quite a few competition prizes and worldwide acclaim. The French auteur Jean-Luc Godard declared him grasp of the “temple of cinema,” whereas the American director Martin Scorsese likened a Parajanov film to getting into “one other dimension, the place time has stopped and wonder has been unleashed.”

Other than symbolism, dazzling colour and crowd pleasing fusions of innovation and archaic motifs, Parajanov’s movies stand out for his or her depiction and celebration of the Caucasus area as one the place numerous peoples commingled and the place aesthetic, literary and creative traditions knowledgeable each other. This can be puzzling to modern readers. Simply as a pasha’s wives pulling toy weapons from their robes is incongruous, on this trendy period of geopolitical tensions throughout Eurasia it appears inconceivable that an Armenian director may shoot a movie in Azerbaijan. The yr after Parajanov shot “Ashik Kerib,” battle broke out between Armenians and Azerbaijanis and the 2 peoples have been at loggerheads ever since, culminating within the flight of the Armenian inhabitants of Nagorno-Karabakh after Azerbaijan’s army marched on the beforehand Armenian-administered territory in late 2023.

But Parajanov labored in and portrayed a realm — from Ukraine’s Carpathian area, via Moldova, to Georgian mountaintops and Armenian monasteries — that was not circumscribed by slender nationwide boundaries or nationalist enmity. The broader Caucasus area is considered one of extraordinarily wealthy folklore and vibrant storytelling, traditions which were knowledgeable by pre-Christian Armenian and Georgian epics, myriad indigenous in addition to Greek and Persian mythologies, and Zoroastrian, Scythian and, later, Turkish and Russian influences. It’s the setting for tales as numerous because the Golden Fleece and the Turkic epic of Dede Korkut, house to the Azerbaijani “ashik” (minstrel) custom (“ashugh” in Armenian) and Ararat, at its southern fringe, is the legendary resting place of Noah’s Ark. Parajanov was steeped within the lore of the Caucasus and alert to its numerous cultures and traditions, making a storytelling model that was beneficiant, animated and ecumenical.

Born into an Armenian household, raised in Tbilisi, and creating early works in Ukraine, Parajanov famously acknowledged, “All people is aware of that I’ve three motherlands.” His declaration of allegiance(s) is reciprocated by every of his designated “motherlands.” Yerevan, the Armenian capital, is house to the Sergei Parajanov Museum; a avenue in Outdated Tbilisi is called after him; and the Ukrainian World Congress, noting the one hundredth anniversary of his delivery, claimed him as “the Ukrainian-Armenian movie director.” This magnanimous identification with a number of “motherlands” arises from a time when maybe nationwide boundaries weren’t as clear-cut as immediately’s nationalists would have us imagine, and when ethnically homogeneous nation-states (as popularly imagined at current) didn’t exist.

Parajanov grew up within the creative milieu of Tbilisi, a metropolis that has been a gathering place of peoples for hundreds of years. Georgian artwork critic Giorgi Gvakharia describes Tbilisi “as a bridge between Asia and Europe,” the place cultural cross-pollination has created a metropolis akin to “a carpet that transforms an eclectic sample into a creative picture.” James Steffen, in his seminal examination of Parajanov’s life and work, contends that Tbilisi’s “cosmopolitan ambiance” and “the wealthy intersection of cultures in Transcaucasia” had been formative influences on the person as an artist and storyteller. Parajanov demonstrated a creative predilection from a younger age. He as soon as remarked, “From the time I used to be a baby, individuals had been at all times screaming that I used to be proficient.” His first forays had been in music; he enrolled on the Tbilisi State Conservatory, finding out voice and violin, earlier than he moved to Moscow in 1945 and gained a much-sought-after place on the State Institute of Cinematography.

Whereas Parajanov and his work could usually be related to the creative and cultural milieu of the Caucasus, his eye was attuned to stimuli from a a lot wider area. Shot on location in Moldova, his diploma film on the Institute of Cinematography was primarily based on a fairy story by Moldovan writer Emilian Bukov. In an essay revealed some years later he wrote that the catalyst was studying this story of a “shepherd who had misplaced his flock — the image of affection and success — in Georgia, Armenia, and … the Carpathians.” No model of the unique diploma movie has survived, however Parajanov later reworked it right into a characteristic movie titled “Andriesh,” wherein the titular character, guardian of the village’s sheep, receives a present of a magic flute. Black Storm, an evil sorcerer enraged by the “joyous music” of the flute, steals the flock and Andriesh units out to retrieve them.

Parajanov was in a position to full this diploma film regardless of the homicide in Moscow of his first spouse, a Tatar lady named Nigyar Kerimova, allegedly by the hands of her family. Plainly Parajanov very hardly ever talked about these occasions, though Steffen notes that he sometimes visited her grave in Moscow in later years. Maybe with a view to cope with his devastation, Parajanov departed Moscow for Kyiv, the place he encountered new creative idioms. He later wrote that he discovered inspiration in “people carving, stitching, metalwork. Historical songs of the Ukraine. I needed to convey the world of those songs in all its primeval fascination.” This spurred in him a quest to plot a medium that conveyed the “poetics” of folktales and mythology.

By his personal estimation, nonetheless, he initially fell wanting this objective. From the late Fifties he directed a number of documentaries and options, however admitted, “[The] little image, Moldavian Fairy Story, is the one considered one of my [early] works whose imperfection I’m not ashamed [of].” He lamented that one movie betrayed “an absence of expertise, craftsmanship and good style.” Movie research students broadly agree. Though Parajanov is now broadly touted as a visionary, his early works are considered run-of-the-mill productions that include some hints of his future however are unremarkable in themselves.

Consensus has settled on “The Colour of Pomegranates,” launched in 1969, as Parajanov’s masterpiece. That is ostensibly an account of the lifetime of the 18th-century ashik Sayat-Nova. Nevertheless, the movie lacks a transparent narrative, linear or in any other case, and dialogue is sort of totally omitted. Quite, the ashik’s childhood, when Sayat-Nova attended the courtroom of the Georgian king and later entered a monastery, is portrayed via what one Soviet journalist described as “cinematic miniatures.” This was, in impact, Parajanov utilizing the “poetics” of fable, symbolism and allegory to maintain and propel a story. The film established a brand new cinematic aesthetic, with the story conveyed via a sequence of extremely stylized situations and still-image compilations of apparently mundane objects quite than a standard narrative. “Handicrafts, clothes, rugs, ornaments, materials, the furnishings of their dwelling quarters — these are the weather. From these the fabric look of the epoch arises,” Parajanov wrote. His all-embracing perspective towards cultures and creative stimuli was additionally obvious within the “Oriental” atmosphere of “Pomegranates.” In discussing the movie he mentioned, “The entire foundation of my artwork is Persian miniatures, enamel from Byzantium … quite simple however which possess their very own depths and wonder.”

Tellingly that is additionally probably the most “autobiographical” of Parajanov’s movies. Sayat-Nova was an Armenian born in Tbilisi, simply as Parajanov was. Parajanov shot episodes of Sayat-Nova’s life in Tbilisi’s historic church buildings, mosques and Turkish baths, claiming that he had frequented the identical locations throughout his personal childhood. A bathhouse scene wherein Sayat-Nova as a boy observes bathers — female and male — via a skylight suggests the adolescent’s sexual awakening and maybe a fascination with each genders. Some students contend that the framing and conceptualization of this scene mirrors Parajanov’s personal experiences and alludes to his personal sexuality. He was broadly understood to be bisexual and was imprisoned on prices associated to homosexuality in 1974. Elsewhere within the movie, notions of gender and identification are at instances fluid, most obvious within the casting of Georgian actress Sofiko Chiaureli as each the younger Sayat-Nova and his beloved Princess Ana, amongst different roles.

“Pomegranates” may additionally be categorized as Parajanov’s most pan-Caucasian manufacturing, in that Sayat-Nova, who wrote poetry and songs in Armenian, Georgian and Azerbaijani, is probably the most broadly liked of the ashiks. Valery Bryusov, a translator of Sayat-Nova’s works, lauded him as a poet “who by power of his genius … ceases to be the property of a person individuals however turns into a favourite of all humanity.” Armenian scholar Karen Kalantar contended that Sayat-Nova “embodied the concept of the friendship of peoples [‘druzhba narodov’],” and it’s tempting to treat Parajanov in the identical mild. James Steffen argues that Parajanov noticed himself, like Sayat-Nova, as a “poet of all Transcaucasia.”

The coexistence of peoples has been actuality within the Caucasus for hundreds of years. Tbilisi was not alone amongst cities of the Caucasus in having a multicultural historical past. Yerevan, the capital of Armenia, had a Muslim majority till World Struggle I, whereas the strongly Azerbaijani identification of Baku has emerged solely for the reason that finish of the Soviet period. The early twentieth century noticed huge upheavals and the displacement of complete communities, which go a way towards explaining modern-day interethnic resentments. Nevertheless, traditionally, on a regular basis intercommunal engagement within the Caucasus noticed materials and non secular lives overlapping as completely different peoples shared rituals, holy figures and holy locations. Emigre Circassian historian Aytek Namitok noticed in 1935 that “frequent shrines revered by followers of each [Islam and Christianity] are in no way uncommon,” and Soviet ethnographer Ivan Meshchaninov famous that “a single pir [Muslim holy man] may discover collectively amongst [his] worshippers the Turk, Armenian, and Georgian.”

Scholar of the Caucasus Thomas de Waal depicts the area as poised, at instances uncomfortably, between continents, political methods, empires and spheres of Christian and Muslim affect. From the sixteenth century, Ottoman Turks and Persians tussled for management of the area. The Russian Empire conquered and subdued it via the course of the nineteenth century, with rule passing to the Soviet Union within the Nineteen Twenties. Through the Soviet interval, ethnic minorities had been acknowledged within the Caucasus, as elsewhere inside the USSR, and assimilation of non-Russian populations was actively discouraged. De Waal notes that from the Sixties the Caucasian republics of Armenia, Azerbaijan and Georgia loved a creative heyday as Moscow loosened inventive restrictions. One Azerbaijani poet described it as a “interval of small renaissance within the Soviet Union.”

Following the success of “The Colour of Pomegranates,” Parajanov, who was in his creative prime, ought to have benefited from such a “renaissance,” however he was to enter considered one of his most difficult intervals. He had lengthy incurred the wrath of Soviet authorities. Earlier, dwelling in Ukraine, he had grow to be concerned in native politics, notably advocating for Ukrainian intellectuals who had been arrested, which led to the Soviet safety equipment viewing him as a dissident. This was not helped by his insistence through the manufacturing of his 1965 characteristic film, “Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors,” that dialogue must be in a dialect of Ukrainian, quite than dubbed into Russian, as typically occurred within the USSR. The film, a story of doomed love among the many Hutsul individuals of Ukraine’s Carpathian Mountains, had been his first vital success. It was additionally the primary time he had efficiently amalgamated the “poetics” of folks mythology into an interesting cinematic idiom. Screening throughout Europe and North America, the movie gained a number of competition prizes and was applauded by one French newspaper as “a museum of folks arts and traditions reworked right into a Chagall portray” and described in Le Monde as a “pure poem.”

Worldwide acclaim, nonetheless, didn’t make for a simple time at house. Despite the fact that Parajanov was Armenian, considered one of his colleagues recalled him quipping, “There’s a gathering of Ukrainian nationalists at my place. … I’m obliged to obtain them! … For them I’m the top Ukrainian nationalist!” Such a remark illustrates Parajanov’s cheeky persona and antiestablishment bent. This, inevitably, led to confrontations with Soviet authorities.

After the breakout success of “Shadows,” his subsequent venture was to have been a long-dreamed-of movie about Kyiv. He accomplished a literary state of affairs, entitled “Kyiv Frescoes,” and display exams that reveal progressive methods and vivid colour and imagery, however the venture by no means gained requisite approval. Parajanov’s headstrong persona and the controversies that he aroused ultimately made his place within the Kyiv movie studio untenable and he moved to Yerevan, the Armenian capital, the place he made “Pomegranates.” But regardless of the acclaim this movie gained, it, too, raised the ire of filmmaking institutions in Moscow and Armenia. Officers initially welcomed the venture on the understanding that Sayat-Nova embodied the friendship of the Caucasian peoples, an concept appropriate with the doctrine of Soviet Realism, which guided all creative endeavors within the USSR and pressured the propagation of unambiguous revolutionary messages. The top product, nonetheless, was described by one script editor as “incomprehensible and unclear,” with one other official lamenting that it might fail to tell audiences of “the actual life journey of the good poet of Transcaucasia,” thus totally lacking a possibility to construct brotherhood within the wider Soviet group.

Parajanov was wilful and capricious and ensuing clashes with authorities considerably hindered his profession, obvious in a string of unrealized scripts: “Confession” (a largely autobiographical evocation of Outdated Tbilisi), “Ara the Honest” (primarily based on an historical Armenian legend), “The Slumbering Palace” (from a Pushkin poem in regards to the Crimean Tatar capital of Bahcesaray) and “The Demon” (an adaptation of Mikhail Lermontov’s self-described “Oriental story”). This listing highlights Parajanov’s attribute embrace of numerous cultural and creative sources, however none of those tasks went into manufacturing. He was arrested, on largely concocted prices, in 1973. He remained in jail in Ukraine for over 4 years, solely gaining his launch after French communist poet Louis Aragon petitioned Soviet chief Leonid Brezhnev. Even then, his tribulations didn’t finish. He returned to Tbilisi, remained with out work for some years and was imprisoned once more in 1982, however this time was swiftly launched.

Because the reform period dawned within the USSR, nonetheless, Parajanov was readmitted into the fold. He was invited to direct a manufacturing of the much-loved Georgian story, “The Legend of Suram Fortress.” The movie was launched in 1985, over 15 years after “Pomegranates.” In a parable a couple of youth being immured in a citadel that regularly collapsed throughout development, Parajanov threaded a plethora of symbols, artifacts, motifs and characters from throughout the Caucasus, from Christian, Muslim and pagan traditions. This regional tour de power featured rugged mountain landscapes, jugglers, the legendary Georgian metropolis of Gulansharo, oriental carpets, minstrels brandishing the “tar” (Azerbaijani lute) and “kamancha” (Persian violin), entreaties to St. Nino, Georgia’s patron saint, and puppets of Amiran, whom the Greeks know as Prometheus. As James Steffen argues, Parajanov associated a distinctly Georgian story however highlighted the numerous overlapping cultural influences that inform Georgian identification.

After “Suram Fortress” Parajanov was to make just one extra movie, “Ashik Kerib.” The concept got here from an eponymous Turkish fairy story that Parajanov remembered listening to as a baby. In attribute model, he evoked a spread of moods and aesthetics in his remedy of the story. It strikes via moments of pantomime-like farce to contemplative pictures of Persian miniatures and components of Sufi lore (“Minstrels solely die on the highway”). Alone amongst Parajanov films, it has a cheerful ending, with the titular ashik returning house after 1,000 days of wandering to win the bride he had beforehand been denied. In an interview with the artwork journal Movie Remark, Parajanov joked, “It ends like an American film!”

The movie was shot on location in Azerbaijan and the dialogue recorded in Azerbaijani, however, as was his wont, Parajanov revealed a various palette of cultural influences, from the joined “Persianate” eyebrows of feminine characters to the soundtrack that juxtaposed Georgian church music with Azerbaijani “mugham” (improvised modal melodies). Scholar of Russian literature Peter Orte observes that the Azerbaijani authorities has tried to train possession over the story of “Ashik Kerib,” transferring to “management its distribution and illustration outdoors Azerbaijan’s borders.” The concept that a story may be commandeered or possessed by a single individuals or state would certainly be anathema to Parajanov. Certainly, the endeavor is questionable at finest as a result of, as Orte highlights, the story exists in lots of iterations — Azerbaijani, Armenian, Georgian, Turkish, a Russian retelling — that means it’s “in the end of combined, or shattered, origin” and thus repudiates “any try to say it for a ‘pure’ nationwide … custom.”

Problems with ethnic and nationwide identification got here into sharp focus because the filming of “Ashik Kerib” was nearing completion. In 1988, rising civil strife between Armenians and Azerbaijanis ultimately led to hostilities in Sumgait, Azerbaijan. Parajanov was mentioned to have been shocked by these occasions. Ongoing battle made all of the extra poignant sure scenes that he insisted on together with within the movie, wherein a bunch of kids supply the Muslim hero shelter in a church earlier than an icon of St. George and defend his “saz” (lute) from marauding Turkish horsemen. This looks like Parajanov’s plea for tolerance and intercommunal engagement and totally shows his ecumenical instincts.

Like the sooner Caucasian movies, “Ashik Kerib” gained widespread worldwide acclaim. And for the primary time ever, Parajanov was in a position to journey outdoors the USSR to attend movie festivals throughout Europe. Rising rigidity within the Caucasus led to the outbreak of battle within the Nagorno-Karabakh area of Azerbaijan and delayed the discharge of the movie in Armenia till effectively after Parajanov’s premature demise from lung most cancers in 1990. We’d declare, nonetheless, that Parajanov had the final giggle: A yr earlier he had been invited to Turkey, Azerbaijan’s staunchest ally, the place he attended the screening of “Ashik Kerib” on the Istanbul Movie Pageant, successful the affections of Turkish cinephiles and a particular jury prize for “contributions to modern artwork.” And a few 30 years later, an exhibition of his collages, costumes, drawings and images at Istanbul’s Pera Museum drew huge crowds.

His recognition amongst Turks is noteworthy given ongoing tensions between Turkey and Armenia, which stem from the genocide of Armenians within the latter years of the Ottoman Empire. Turkey denies {that a} genocide occurred, whereas nationalist circles generally revile Armenians. The Nagorno-Karabakh battle of the Nineties solely heightened acrimony; Turkey closed its border with Armenia in solidarity with the Azerbaijanis, whom they appear on as ethnic kin. But Parajanov’s artwork impressed and delighted throughout borders and political divides — maybe as a result of he was progressive and ebullient however maybe additionally as a result of he was open-hearted in his embrace of numerous cultures, rituals, symbols and mythologies, and benevolent in sharing them along with his audiences.

The centenary of Parajanov’s delivery affords a vantage level from which to reappraise, inside the context of sociopolitical adjustments which have unfurled throughout the Caucasus, his standing as a visionary cinema auteur and teller of tales from throughout the area. In the end, Parajanov’s creative output was distinctive in imaginative and prescient and creativity however circumscribed by the rigidities of Soviet political circumstances. Like Parajanov’s very life, his work absorbed and was influenced by and mirrored the kaleidoscopic creative conventions of Eurasia. We’d argue that he must be anointed a modern-day Sayat-Nova. Each created much-loved works in Armenian, Azerbaijani and Georgian, works that illustrate how the cultures, traditions and every day lives of the peoples of Transcaucasia had been as soon as interwoven to an extent that’s laborious to think about at present. As Parajanov as soon as acknowledged, “The cultures of peoples, particularly of neighbors, are vessels for speaking with one another. Artwork, and first of all cinema, as the preferred artwork type, ought to additional the mutual drawing collectively of individuals.” Along with his generosity of spirit and his startling creative imaginative and prescient, Parajanov certainly succeeded on this.

The strictures of Soviet management have since been lifted, however the Caucasus is now marked by closed borders, nationalist rancor, polarized communities and disputes over “possession” of what must be shared cultural legacies. That is the very antithesis of Parajanov’s world and inventive imaginative and prescient. Given present geopolitical realities, it’s extremely unlikely anybody may ever observe in his footsteps, drawing from numerous cultural touchstones and successful applause throughout worldwide boundaries. Maybe this makes him — if he wasn’t already — inimitable.

Turn out to be a member immediately to obtain entry to all our paywalled essays and the most effective of New Strains delivered to your inbox via our newsletters.